|

|

The Settlement of Iceland in the Viking Age

The settlement of Iceland in the Viking age is a story that illustrates many aspects of Viking-age culture and mindset. It is a story that is told in some detail by literary sources and more sketchily by archaeological sources. The two main sources agree on some points, but disagree on many others. In this article, I will summarize the story as told by the literary sources (such as Landnámabók, the book of settlements, and Íslendingabók, the book of Icelanders) and point out areas where archaeology paints a different picture.

Exploration. As were many of the Norse discoveries in the North Atlantic, Iceland was discovered by accident. Sometime in the second half of the 9th century, a Viking named Naddoddur left Norway in his ship intending to make landfall in the Faroe Islands. He was blown off course and came to the coast of an unknown land. He went ashore, climbed a mountain, and saw no smoke, and so concluded that the land was uninhabited.

Naddoddur sailed back home and told others. Garđarr Svávarsson returned to the land and sailed around it to prove it was an island. He had many good things to say about the land, noting it was "wooded from the mountains down to the sea".

|

Flóki Vilgerđarson (left) sailed to search for Garđar's island in the late 860s. He brought ravens with him, releasing the ravens as he sailed. When one flew up in to the air and didn't return to the ship, he followed the raven's course to the new land. Flóki and his crew ran in to many difficulties during their visit, and it was several years before they could return to home to Norway. |

|

During one of his winters in Iceland, Flóki climbed the mountain Hornatćr (shown as it appears today in summer) and saw nothing but snow and a fjord full of ice, and so he called the land Ísland (ice land), and the name stuck. When he returned home, he had little good to say about the land, but his crew reported that every blade of grass dripped with butter, an attractive image at a time when butter was the means for long-term storage of excess dairy production, representing wealth and easy living. |

|

These explorers found a land that met virtually all their needs for settlement. Coastal regions and inland valleys were fertile and suitable for the kind of farming they would have been familiar with in their homelands. Extensive meadowlands provided fodder for livestock, and woodlands provide wood for buildings, fuel, and even for ship building. Bogs provided turf for buildings and iron for smelting. Underground volcanic activity provided hot springs for washing and bathing. Birds, fish, and sea mammals provided food and raw materials. Since the only native land mammal was the arctic fox, there were few predators for livestock.

What was more remarkable is what was not found: any signs of human habitation. Why had Iceland not been settled before this time?

Lands both to the east (such as Greenland) and to the west (Scandinavia and the rest of Europe) were settled for thousands of years before the Viking age. Why not Iceland? There is no clear answer.

The literary sources say that the first explorers found evidence of papar, Christian hermits thought to be from Ireland. Other contemporary sources suggest these hermits traveled to the Orkney and Faroe Islands in curachs (skin boats with twig frames) for solitary meditation before returning home. Perhaps some of them reached Iceland. If these people did reach Iceland, it would not be surprising they would flee at the sight of a Viking ship, being all too familiar with the raiding practices of these Northern seamen.

|

Place name evidence also suggest the presence of these Irish visitors, called papar. The photo to the left shows Papafjörđur in east Iceland (fjord of the papar). A number of ruins were thought to be built by Irish hermits, such as the Írskra búđir (Irish booths) in west Iceland shown to the right. Yet archaeological evidence shows these and other similar ruins all postdate the settlement. |

|

|

Some very early artifacts have been found in Iceland, including these Roman coins from the 3rd century, as well as early 9th century beads and broaches, but there is no evidence to suggest that they were lost or buried any earlier than the time of the first explorers and settlers. |

(Recent reports in the popular press suggest that some artifacts have been found in a pre-settlement context. Until these reports are confirmed in an archaeologists' report, I have to discount them.)

So it seems these Viking-age explorers did, indeed, find an attractive, uninhabited land, ripe for the taking. It must have been an irresistible draw for Viking-age Norwegians who were becoming more and more uncomfortable with their situation at home.

|

Settlement. The literary sources say the settlement began in earnest around the year 870. Two foster-brothers, Ingólfur Arnarson (right) and Hjörleifur Hróđarsson, had killed the son of an earl, and were forced to leave Norway. They traveled to Iceland to explore the land described by Flóki, then returned to Norway to mount a settlement expedition. They gathered: supporters and family to travel with them; tools, supplies and livestock so they could be self-supporting from the moment they stepped ashore; and importantly, ceremonial items that would define their new home. |

|

|

The two foster-brothers sailed together, but lost sight of each other before reaching land. When Ingólfur saw the coast of Iceland, he threw his high-seat pillars (öndvegissúlur) overboard. At his home in Norway, these carved wooden pillars flanked Ingólfur's seat as the head of his household. Ingólfur said he would settle wherever the pillars washed ashore, implicitly asking the Norse gods for guidance to find a site that met the approval of the protective land spirits (landvćttir) who inhabited the land. When he landed, Ingólfur directed his slaves to look for the pillars. |

|

Hjörleifur did not worship or sacrifice to the gods, and he took no such precautions. He landed at Hjörleisfhöfđi (right, as it appears today), built two houses, and began to farm. His slaves revolted and killed Hjörleifur and everyone on the farm. When Ingólfur heard the news and traveled to the site, he commented that it was a sad end for a valiant man, but it's what happens to someone who doesn't worship. Ingólfur tracked down and killed the renegade slaves. |

|

|

Ingólfur and his slaves continued to search for the pillars. During the third year, they found them washed ashore at the present site of the city of Reykjavík. Here, Ingólfur built his home. His slaves were unimpressed, saying, "It’s not much use our traveling across good country, just so we can live on this remote headland." Landnámabók gives the date as 874. |

| The date is supported by the science of

tephrochronology, which

allows buried artifacts to be dated by layers of ash laid down by

Iceland's volcanos.

A Viking-age house recently was excavated under the streets of Reykjavík, close to the probable location of Ingólfur's farm based on literary sources. One of the important ash layers in Iceland is called the settlement layer, deposited around the year 872. The house postdates this layer, but one of the walls (right) that enclosed the fields close to the house predates it, suggesting that the date in Landnámabók is not off by more than a year or two. |

|

|

Ingólfur was followed by many thousands of his countrymen over the next few decades. The literary sources suggest that Iceland was settled by wealthy and influential men and women who left Norway because of the increasing political ambitions of King Haraldur inn hárfagri (the fair-haired). Haraldur (left) took over the throne from his father at the age of ten, and he resolved to unify Norway under his rule. |

In solidifying his control over the petty kings, earls, and chieftains who ruled Norway, Haraldur claimed their land and possessions (óđal) as his own, and appointed his own men in each district to collect taxes and administer the law. Óđal was the right of free farmers to own their land, and it distinguished a free man from a slave. It seems very likely that the leading men in the district no longer felt they were their own masters under these conditions and might look to emigrate to escape the Haroldur's tyranny.

Even if Haraldur's actions are overstated in the literature, it appears that Iceland's settlement were led by families that were wealthy enough to outfit a settlement expedition, powerful enough to have enough followers to make the homestead claim viable, and independent enough to give up their familiar home for an uncertain future on a remote island.

Not every settler was a wealthy Norwegian, and not every settler opposed the king. Some may have left for a new home because they had few prospects in Norway. Some had little choice in the matter, being slaves and tenants that traveled with the master's household.

The stories say that most of the settlers came from Norway and from Norwegian settlements in the British Isles. DNA analysis confirms the literary sources. 80% of the male Icelandic ancestry derives from Nordic lands, but 62% of the female ancestry derives from the British Isles. Men from Norway might harry or even settle in the British Isles and North Atlantic islands before continuing to Iceland. During their visit, they might marry in to local families in order to seal alliances, or they might pick up slaves and concubines.

|

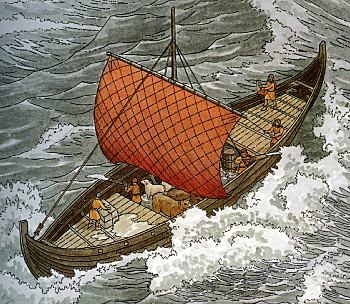

Settlers traveled on knörr, Viking cargo ships optimized for cargo capacity, rather than for speed. The voyage from Norway to Iceland was expected to take a week or two, but some extraordinary voyages took much longer. |

|

Landclaims. Upon arrival, the settler claimed the land by exploring it, naming key features, and building their homes. Then, through gift or sale, the settlers distributed their land, granting portions of their claims to their crews, supporters, and family members to build up a band of supporters and to gain authority over the district as the chieftain (gođi). The chieftain not only was the leading man for the district, he was the point of contact for the government, and also the priest for the pagan religion, building the temple and conducting the rites. He physically surrounded himself with family, friends, and supporters who were prepared to offer armed assistance, should it be necessary in a dispute.

Íslendingabók says that the around the year 930, the land was fully settled. All the arable land had been claimed. At that time, the population is thought to have been around 25,000 people. Yet settlers continued to arrive. These later arrivals had to acquire land from the earlier settlers, through purchase, or as a gift.

|

Gísla saga says that Ţorbjörn súrr arrived in Dýrafjörđur from Norway in the year 952, when the land was fully settled. Landnámabók says that Vésteinn Végeirsson gave him half of the land in the valley Haukadalur (left), but Gísla saga says Ţorbjörn bought the land. Haukadalur (left, as it appears today) is highly desirable land, but some later settlers had do make do with much less. |

|

When Önundur tré-fótr (wooden-leg) arrived, he was told that little unsettled land was still left. He bought land under Kaldbakur (cold-back mountain, right), dismayed by all he gave up in Norway only to gain a cold-backed mountain. |

|

Archaeological sources. In recent years, studies of land settlement and farm boundaries suggest a carefully planned and executed settlement. The patterns suggest that the first settlers searched for ideal locations to establish "core" settlements that had all the resources they needed to establish a working farm during their first years. The looked for a site with wet, open meadowlands near the coast that produced the best fodder for the livestock and the best turf for buildings and which didn't require clearing the land of trees. They looked for resources like bird colonies and fishing grounds for quick access to food, and for islands where livestock could be left to graze safely and multiply.

|

Once the core settlement was established, many additional farms were created, filling a region such as a valley. In what appears to have been a carefully laid out plan, land was divided to give equal resources to each farm. For example, the settlement-era farms in Öxnadalur, an inland valley in north Iceland, are uniformly spaced on both sides of the river (left). This kind of uniformity was probably not random, but more likely, was planned and controlled. |

| Today, Öxnadalur continues to be a valley dotted with farms (right). When the settlers arrived in these new areas, the land was almost certainly forested, and so these later farms were cleared by setting fire to the forest. Charcoal layers found under these settlement era structures today attest to that approach to land clearing. |

|

Other resources seem to have been created for the sole purpose of establishing the farms and making them productive as quickly as possible. Once the farms were established, these resources were abandoned. For example, an early iron-producing site in west Iceland appears to have produced prodigious amounts of raw iron, enough for dozens of farms, but only for a few seasons before being abandoned.

This and other evidence suggest that thought and planning went in to locating and establishing the settlements, indicating the presence of a leader with some authority and possessing significant resources.

While the literary sources present a neat and coherent picture of the settlement, other evidence casts a shadow of doubt on the stories. We may never know the full story, but the research continues.

|

|

©2014-2026 William R. Short |